Introduction

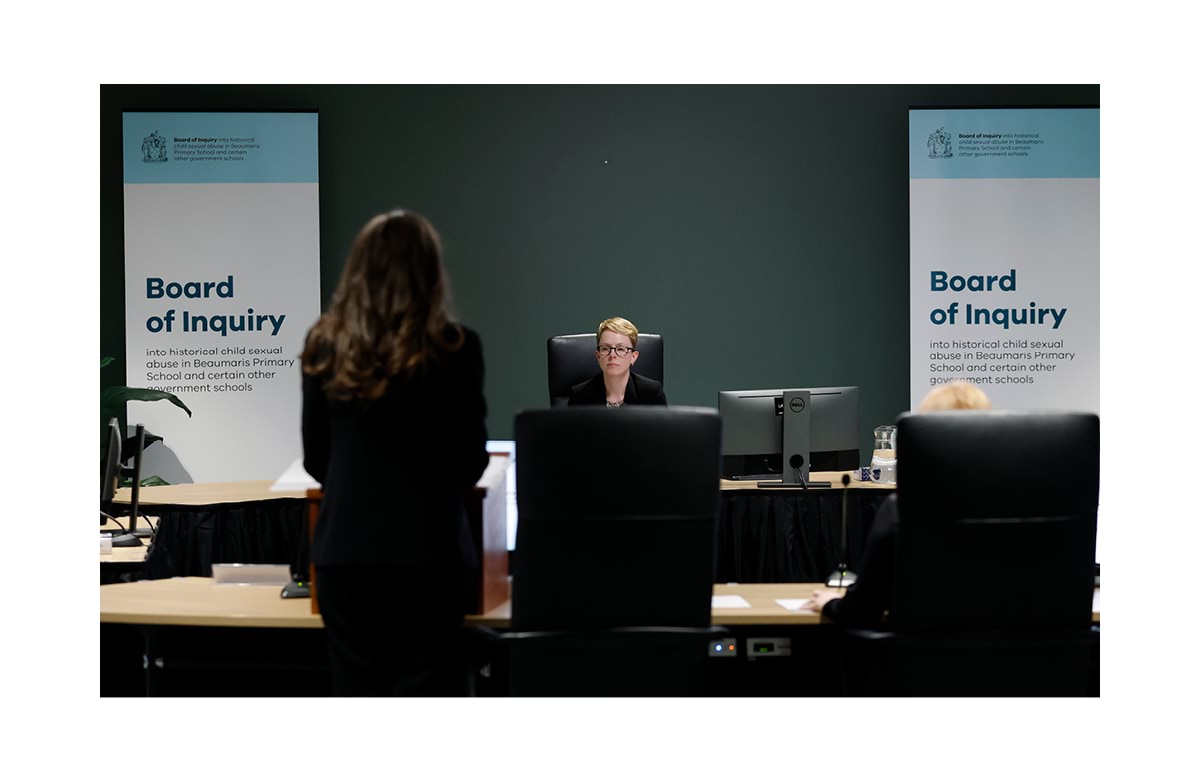

Following persistent advocacy from victim-survivors, on 28 June 2023 the Victorian Government announced a Board of Inquiry into historical child sexual abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and certain other government schools. This Chapter describes the process of establishing the Board of Inquiry and how it approached its work.

From the start, the Board of Inquiry was firmly committed to ensuring it worked in ways that were inclusive, welcoming and sensitive to the trauma and distress associated with child sexual abuse. This Chapter describes the approach the Board of Inquiry adopted in designing and delivering its functions. This included a participant care and support model that was personalised to victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members. This personalised model was important to ensure the inquiry not only avoided re-traumatising participants but actively contributed to their healing and recovery.

The Chapter concludes by describing the steps taken to raise awareness of the Board of Inquiry’s work and the various ways information was gathered and presented to inform this report and recommendations.

Establishment

For some time, a group of individuals steadfastly advocated for closer examination of historical child sexual abuse allegedly perpetrated in Victorian government schools. A number of these advocates shared experiences of sexual abuse that occurred while they were students at Beaumaris Primary School during the 1960s and 1970s. They wanted an inquiry that could support victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools to obtain answers about how such abuses could have happened and remained undetected or tolerated for so long. They also wanted their pain and suffering acknowledged as a step towards recovery and healing.

Inquiry announced

On 28 June 2023, the then Premier of Victoria, the Hon Daniel Andrews, announced the establishment of a Board of Inquiry into historical child sexual abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and certain other government schools. The inquiry was designed to ‘focus on a significant cluster of known abuse at Beaumaris Primary School, as well as other government schools where the same former employees worked, in the 1960s and 1970s’.1 The Board of Inquiry was required to report back to the Government by 28 February 2024.

One victim-survivor present at Mr Andrews’s announcement reflected:

There’s been a lot of people involved in this, to get it to this stage. It’s about all of those people — people who have lost their voices, people who haven’t found theirs yet. I know of three people who aren’t with us anymore, so I sort of really feel that we need to just speak for them. They’ve got nothing left and their families are missing loved ones because of events that took place in their childhood, and it’s just not right.2

Mr Andrews acknowledged: ‘This inquiry won’t undo their pain, but we hope it gives victim-survivors the recognition and support they deserve’.3

Chair appointed

On 28 June 2023, the Lieutenant-Governor, on the recommendation of the then Premier, appointed Victorian barrister, Kathleen Foley SC, to lead the Board of Inquiry under section 53(1) of the Inquiries Act 2014 (Vic) (Inquiries Act).

Ms Foley was called to the Victorian Bar in 2009 and was appointed Senior Counsel in 2021. She was appointed to the Victorian Law Reform Commission in November 2020 as a part-time commissioner, a position she holds while continuing her work as a barrister. During her time at the Victorian Bar, Ms Foley has served as a member of the Victorian Bar Council and as a member of the executive of both the Commercial Bar Association and the Women Barristers Association. Ms Foley’s practice at the Bar is diverse and has included work involving institutional child sexual abuse.

Prior to her admission to the Victorian Bar, Ms Foley worked as an attorney in New York and as a solicitor in Western Australia. She was also an Associate to Justice Hayne AC of the High Court of Australia. In 2016, Ms Foley was awarded the Victorian Bar’s Susan Crennan AC KC award for her pro bono work. She holds a Master of Laws from Harvard Law School, and a Bachelor of Laws (Honours) and Bachelor of Arts from the University of Western Australia.

CEO and Board of Inquiry staff appointed

Nicola Farray was appointed as CEO of the Board of Inquiry in July 2023. As CEO, she employed a multidisciplinary team from a range of sectors and professional backgrounds. Ms Farray was committed to bringing a collaborative and innovative approach to the Board of Inquiry’s work, building upon her prior experience in inquiries and royal commissions, as well as her experience in the fields of public administration and social work.

Thirteen staff worked across three teams: Operations and Executive Support Team; Policy, Research and Strategy Team; and Communications, Engagement and Supports Team. The Board of Inquiry established a Legal team with lawyers from Corrs Chambers Westgarth who supported Counsel Assisting and acted as the Board of Inquiry’s solicitors.

Team members brought varied and diverse expertise to their work with the Board of Inquiry. In addition to their formal experience, staff and members of the Legal team were recruited with particular attention to their values and ability to interact with others with care, sensitivity and compassion.

More information about the structure and operations of the Board of Inquiry, including the operational structure of the team and the role the various teams played is in Chapter 2, Operations(opens in a new window).

Counsel Assisting appointed

Fiona Ryan SC, Kate Stowell and Mathew Kenneally are Victorian barristers and acted as Counsel Assisting for the Board of Inquiry. Counsel Assisting performed many critical functions for the Board of Inquiry and performed leading roles in private sessions and public hearings. During public hearings, Ms Ryan SC and Ms Stowell made opening and closing statements, led evidence and questioned witnesses. Ms Stowell and Mr Kenneally each conducted private sessions as part of the Board of Inquiry’s work, as did the Chair. This involved trauma-informed information-gathering.

Information from the public invited

As the Board of Inquiry team was appointed, its initial focus was on establishing policies and processes needed to perform its work. In August 2023, the Board of Inquiry’s website went live, with information about its purpose and scope, along with contact details for media enquiries. The Board of Inquiry established a dedicated phone line and a public email address to receive information from the public. From the outset, the Board of Inquiry made it clear that it was open to receive questions, comments and information from the community.

On 7 September 2023, the Chair held a media conference to open the Board of Inquiry’s public consultation period, inviting submissions and registrations for private sessions. At a later date, as part of the Board of Inquiry’s call for information from the community, the Board of Inquiry publicly named three alleged perpetrators who were understood to have worked at 18 government schools.

On 4 October 2023, having completed preliminary analysis of information received from victim-survivors, the Department of Education and Victoria Police, the Board of Inquiry identified an additional alleged perpetrator and a further six government schools that were within scope. Details of these alleged perpetrators and schools are given in Chapter 3, Scope and interpretation(opens in a new window).

Other establishment tasks

The Board of Inquiry also took steps to secure office space and identify appropriate facilities for private sessions and public hearings. A range of other processes and policies were established to facilitate the running of the Board of Inquiry, including those relating to governance; project planning; budget management; financial and employment delegations; confidentiality and conflict of interest declarations; and onboarding of and provision of induction manuals to staff. Where suitable, the Board of Inquiry replicated government policies and process related to staffing and operational matters, implementing controls where needed to preserve the Board of Inquiry’s independence.

The Board of Inquiry also established a secure, protected IT environment and ran procurement processes for key support services, including document management and counselling and staff support services. More information about how the Board of Inquiry ran is found in Chapter 2(opens in a new window).

A trauma-informed approach

Part of the Board of Inquiry’s task was akin to enabling truth-telling. This responsibility was made clear by the first objective of the Board of Inquiry, as described in the Order in Council, to ‘[e] stablish an official public record of victim-survivors’ experiences of historical child sexual abuse by relevant employees ...’.4

In Australia, truth-telling processes have been led by and for First Nations peoples to formally record evidence about the historic and ongoing impacts of colonisation.5 More broadly, truth-telling can help people move forward in their healing journeys by acknowledging and validating past harms and injustices. As one victim-survivor shared:

I’m grateful that we’re being heard. I’m grateful that people are listening … I hope this sort of sets a precedent to be able to do this in a better way where people can step forward and go ‘This is what happened’ and will be believed.6

The Board of Inquiry adopted an approach that provided victim-survivors with recognition. It did so on the understanding that many had suffered social stigmatisation and been met with scepticism for a long time. To recognise this suffering, the Board of Inquiry heard victim-survivors, gave them the opportunity to share their stories in the way they wished to share them and upheld the dignity of all those who came forward.7

In carrying out this truth-telling aspect of its work, the Board of Inquiry conducted itself in a trauma-informed way, centred on the needs of victim-survivors and on caring for its staff. This approach was underpinned by internationally recognised best practice, including focusing on safety, voice and choice, and trustworthiness and transparency.8 The Board of Inquiry adopted these principles as consistent with its values. The principles are also consistent with the Board of Inquiry’s Terms of Reference, which specifically required the Board of Inquiry to:

- [p]rovide a safe, accessible, supportive, and culturally safe forum for victims-survivors and secondary victims to participate in the inquiry, including accommodating their choices in how they wish to participate in the inquiry, while recognising that some people may not wish to share their experiences;

- [p]rovide sensitive, culturally safe and appropriate trauma informed outreach, mental health and counselling supports for victim-survivors and secondary victims. For any person who approaches the inquiry and wishes to be heard but whose story is not within the scope ... direct the person to an appropriate external mental health, counselling, or support service …9

Following its establishment, the Board of Inquiry engaged with victim-survivor advocates and listened and learned about the factors they felt were important to ensure the Board of Inquiry’s work was accessible, supportive and healing. The Board of Inquiry also considered approaches adopted by similar past inquiries that examined child sexual abuse or other traumatic events, to learn what had worked well or where past processes could be improved. The Board of Inquiry also relied on literature that defined best practice approaches to promoting psychological safety in interactions with traumatised people and communities.

The Board of Inquiry was told that an important part of being trauma-informed is ensuring people feel psychologically, culturally and physically safe. The Board of Inquiry was cognisant that sharing memories of child sexual abuse was highly likely to be traumatic. Such experiences can activate threat responses that are not always conscious nor easily articulated, but can have lasting effects. Therefore, all the Board of Inquiry’s practices focused on creating safety — both actual and felt — in all its conduct and interactions.10

Being trauma-informed was central to all of the Board of Inquiry’s information gathering, including how it engaged with stakeholders, invited and received submissions, managed private sessions, conducted public hearings and approached roundtables and community engagement. The Board of Inquiry also sought to address the needs of individuals from diverse backgrounds and communities, including culturally and linguistically diverse groups, First Nations people, people with a disability, people from various faith backgrounds, and members of LGBTIQA+ communities.

In this section, when we refer to the participant care and support model, the term ‘participant’ is used to refer specifically to victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members.

The participant care and support model

An inquiry is far more than its final report — it is a unique opportunity for a respected authority to hear and acknowledge pain, to validate experiences, to promote accountability and to support closure and healing. For some individuals, it is the compassionate human interactions they have with the people working on an inquiry that are most significant and meaningful to them. For these reasons, the Board of Inquiry wanted to build on the experiences of past inquiries that engaged with people experiencing trauma.

For some, the Board of Inquiry provided an opportunity to speak about their experiences of child sexual abuse for the first time. For others, participation meant revisiting previously shared experiences, which sometimes had not been well-received or properly heard. The Board of Inquiry knew it was crucial to ensure that victim-survivors felt safe to share their experiences of child sexual abuse and their reactions to it, without judgement. Developing or re-building trust — and maintaining this trust throughout the life of the inquiry — was critical to the Board of Inquiry’s effectiveness.

When announcing the Board of Inquiry, Mr Andrews stated that the Board of Inquiry would provide ‘trauma-informed support for people who participate in the Inquiry’11 through a ‘comprehensive support system’.12 As discussed, the Order in Council establishing the Board of Inquiry emphasised the need for the inquiry to provide a supportive and trauma-informed space for victim-survivors. Accordingly, the Board of Inquiry employed a number of staff with professional skills and clinical experience to design and deliver its trauma-informed participant care and support model.

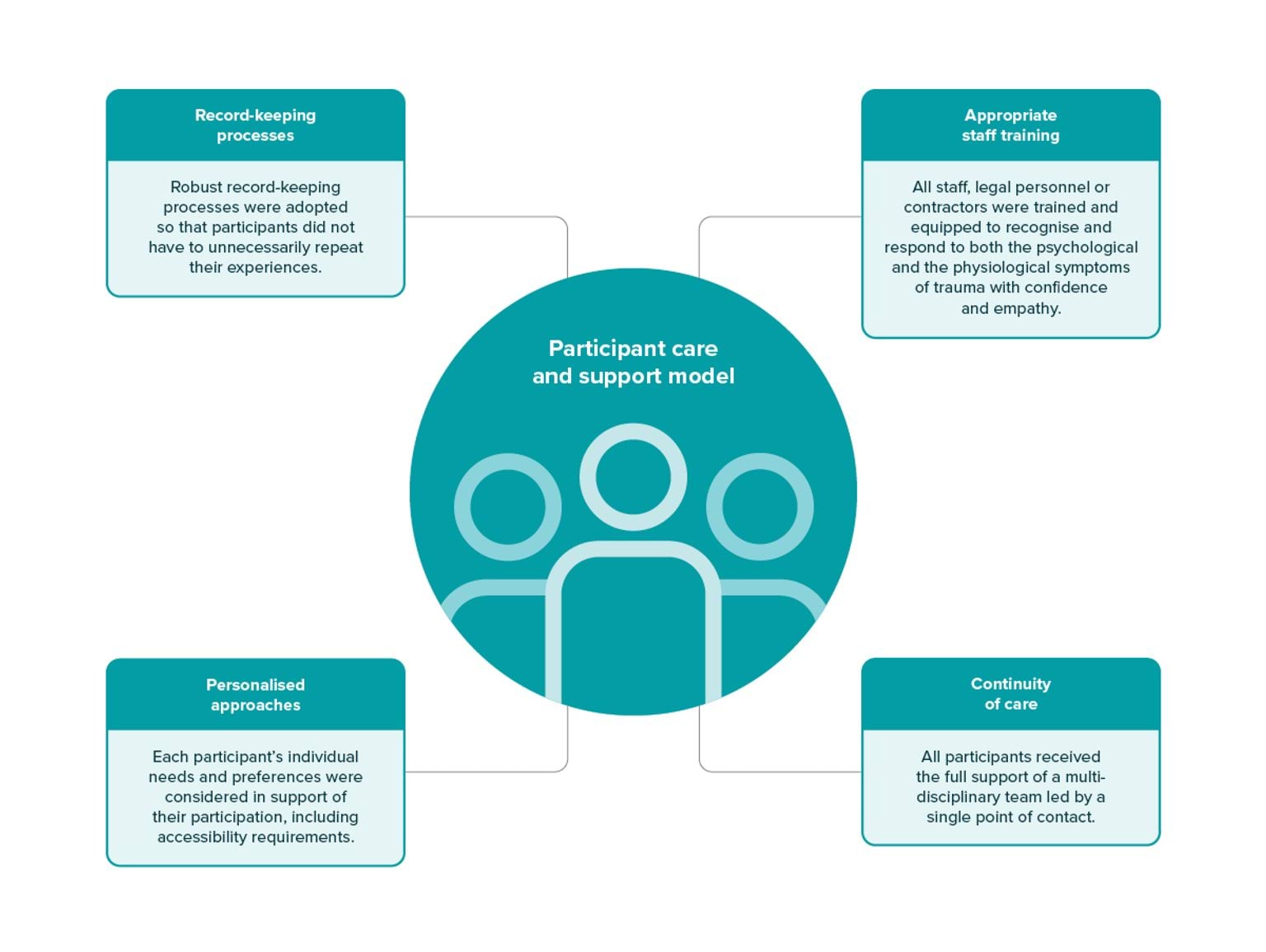

The objectives of the participant care and support model were not only to minimise the potential for re-traumatisation or distress for participants, but to promote choice, control, healing and empowerment at each point in their journey. The model, shown in Diagram 1, has four pillars:

- Continuity of care — The model ensured continuity of care for participants, provided by a multidisciplinary team led by a single point of contact. To enable trust to be established and maintained, the Board of Inquiry drew on methods traditionally applied in a client–therapist model13 to create a model that supported participants through tailored engagement, communication and care and support interventions, all provided by a consistent team.

- Personalised approaches — The Board of Inquiry developed personalised approaches based on each individual’s trauma presentation, needs and preferences. This included considering any accessibility requirements each individual had, to maximise their participation. These personalised approaches were adopted by all staff, members of the Legal team, and counselling providers to create a seamless and cohesive experience for the individual.

- Robust record-keeping — The model included record-keeping processes that minimised the possibility for error or misunderstanding among Board of Inquiry staff, and that avoided the risk of a participant having to unnecessarily repeat sensitive information.

- Appropriate staff training — The Board of Inquiry ensured all staff, legal personnel and contractors were trained and equipped to recognise and respond to both the psychological and physiological symptoms of trauma with confidence and empathy.

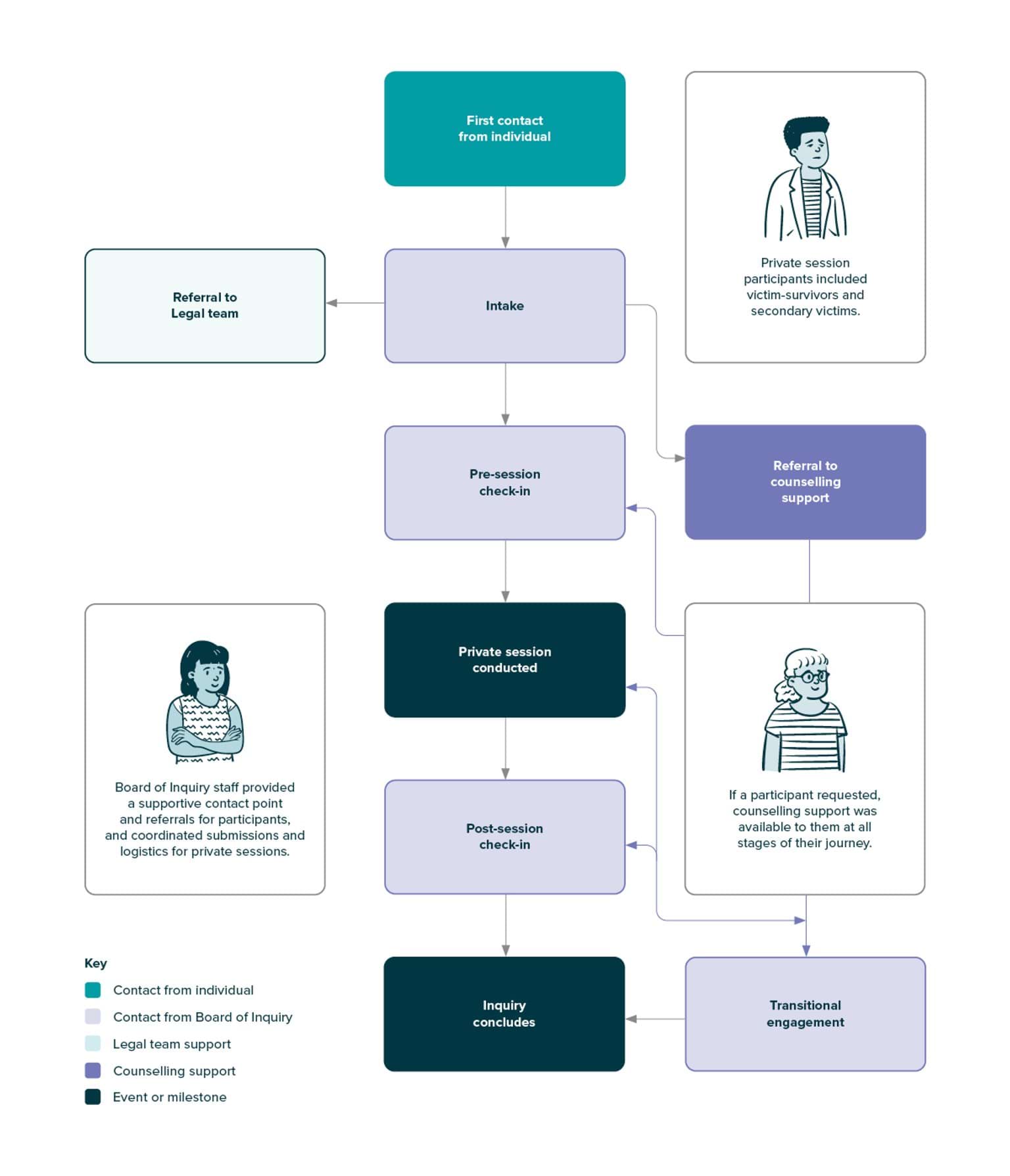

The next section provides an example of how the participant care and support model operated for participants in private sessions.

How the model worked for private session participants

A range of victim-survivors chose to participate in a private session with the Chair or Counsel Assisting. They could also opt to provide a written submission in addition to a private session or instead of one. Individuals were also encouraged to consider which parts of their personal experiences they felt most comfortable and safe to share. Victim-survivors could also elect to provide their information more informally, through conversations with Board of Inquiry staff. Sometimes initial conversations helped build individuals’ trust and confidence, and they later elected to participate in more formal processes.

Individuals who wished to participate in a private session were supported by a dedicated team member to complete an intake assessment. This process helped identify each individual, theirdesired level of engagement with the Board of Inquiry, and the support they may need during the inquiry.

The intake process also helped ensure that the Chair or Counsel Assisting attending the private session could prepare, and avoided the participant having to repeat any information or details they provided at intake, if they did not wish to do so.

If someone booked a private session, Board of Inquiry staff would ensure the individual was clear about the details of the appointment (including providing them with written confirmation) and that they received appropriate support in the days leading up to and following the session. This check-in process helped ensure participant wellbeing. It also helped Board of Inquiry staff facilitate appropriate referrals to the Counselling Support team or Legal team, where needed.

Diagram 2 outlines a typical participant experience pathway for private sessions.

To prioritise the rights, autonomy and preferences of participants in private sessions, Board of Inquiry staff clearly explained to participants the options available to them regarding how the Board of Inquiry used the experiences they shared. For example, the Board of Inquiry could make information public, keep it anonymous (that is, use the information in this report or in hearings, but ensure it was de-identified) or keep it confidential (that is, use the information only for building the Board of Inquiry’s knowledge and not share it publicly, even in a de-identified way). Participants indicated their chosen option as part of the intake process; then, during the private sessions themselves, participants discussed and confirmed their choice with the Chair or Counsel Assisting.

Participants were not locked into a decision about how their information would be used. If a participant changed their mind at any time, from intake to after a private session — for example, if they decided they no longer wanted their experience to be kept confidential — the Board of Inquiry would accommodate that change.

During private sessions, the participants and the Chair or Counsel Assisting discussed how records of the private session would be protected, both during and after the inquiry. For victim-survivors involved in court proceedings in relation to their experiences of child sexual abuse, protection of records was often an important issue to discuss.

The Board of Inquiry also promoted access and inclusion in its processes. When participants had needs that fell outside the Board of Inquiry’s participant care and support model, it referred participants to additional services and supports, such as family violence support services and community mental health services. This helped ensure that the diverse needs of participants were addressed; namely, that they received specialised, integrated and trauma-informed care, how and when they needed it.

Counselling support

As part of its participant care and support model, the Board of Inquiry ensured all participants had access to a range of supports. Tailored, therapeutic counselling was one of these.

Counselling support was provided by a team of dedicated and experienced counsellors from the South Eastern Centre Against Sexual Assault and Family Violence (SECASA).

Counselling support was one-on-one, and focused on supporting participants to manage the effects of revisiting their experiences of child sexual abuse during the inquiry. The service was not designed to address the childhood trauma itself, nor was it intended to act as a crisis support service. Engagement with counsellors was entirely optional.

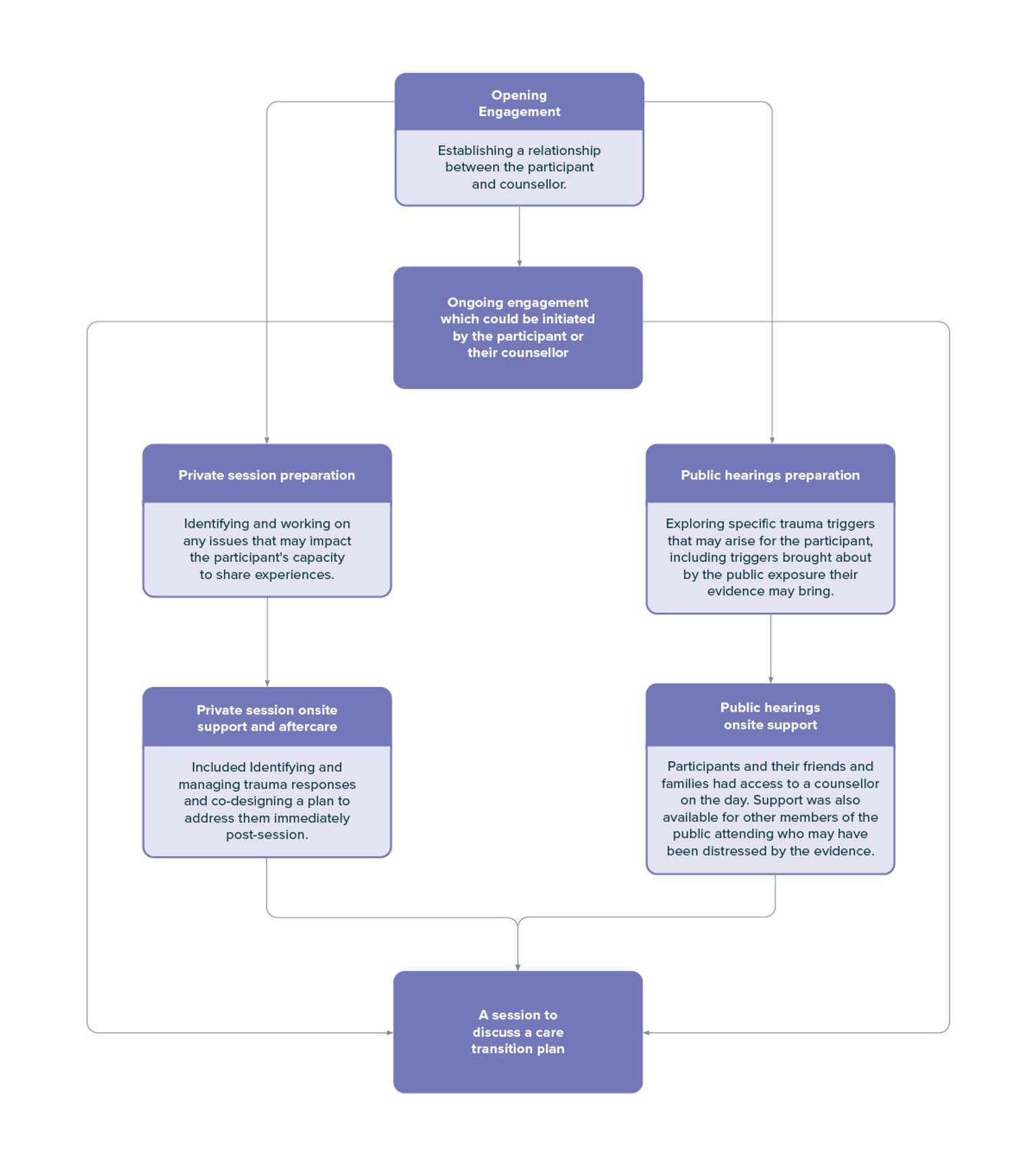

Counselling could be delivered face-to-face or through video or phone calls, based on participants’ needs and circumstances. It generally involved:

- An opening engagement, to establish a relationship between the participant and counsellor. The counsellor would also gently reinforce the objective and scope of the service and explain the Board of Inquiry’s approach to choice and control in information sharing. This opening engagement was also intended to create a shared understanding of difficulties that may arise through participating in the inquiry, including triggers, anxieties or medical conditions, and to explore some possible strategies to pre-empt or manage these difficulties.

- Support for private session participation, which involved the counsellor working with the participant to identify any issues or barriers that may impact their capacity to share their experience at a private session, as well as ways they could navigate through these issues and barriers. Counselling sessions could also include the counsellor and participant discussing how to identify and manage trauma responses and co-designing a plan for addressing them immediately post-session. ‘A guide to private sessions for victim-survivor participants’, which was developed and shared with participants prior to private sessions, can be found in Appendix E, Private sessions(opens in a new window).

- Support for public hearing appearances, which involved the participant and counsellor exploring some of the specific trauma triggers that may arise. This counselling involved encouraging the participant to anticipate and plan for any impacts they may experience and implement strategies for self-care in preparation for the day. ‘A guide to public hearings for victim-survivor participants’ was developed by the Board of Inquiry to help individuals prepare. This is discussed below and found in Appendix E(opens in a new window).

- Onsite support at public hearings and private sessions, which ensured participants had access to a counsellor on the day. In addition to supporting participants (and their friends and families) during public hearings, counsellors were available to support other members of the public attending who may have been distressed by the content of the hearings.

- Ongoing engagement, which could be initiated by a participant or their counsellor. Counsellors offered ongoing support that covered self-care skills, emotional regulation and anxiety management. Counsellors also actively monitored how participants seemed to be coping to identify whether they required more immediate treatment, care and support. Other events (for example, media coverage) were actively monitored to anticipate triggers that may result in the need for additional support.

- A session to discuss a care transition plan. The purpose of the care transition plan was to manage the conclusion of the counselling support provided by the Board of Inquiry and arrange any referrals for external or ongoing support that the participant may need. This session was designed to support closure and debriefing and to help the participant and counsellor end the counselling relationship on good terms. The session also provided the counsellor with an important opportunity to review existing supports for the participant and their family and to discuss any need for ongoing supports.

Diagram 3 outlines a typical participant counselling support pathway.

As the Board of Inquiry neared its conclusion, it commissioned three webinar presentations to provide participants and other engaged victim-survivors with an enduring resource to support their respective healing journeys. The presentation topics included recognising trauma triggers and utilising techniques to manage these; the role and practical application of self-care; and strategies for managing shame.

Other supports and referrals

A range of other supports were available for people who engaged with or were affected by the Board of Inquiry.

Board of Inquiry staff connected people to information sources, services and advocacy bodies so that they could access relevant support, make a report regarding child sexual abuse or seek other assistance.

Individuals were primarily directed to:

- sexual assault support services, including the Centre Against Sexual Assault, Sexual Assault Services Victoria and Bravehearts

- legal advisory services, including Victoria Legal Aid and the Federation of Community Legal Centres

- reporting bodies and authorities, including the Victoria Police Sexual Offences and Child Abuse Investigation Team and the Department of Education Sexual Harm Response Unit

- the National Redress Scheme

- mental health and trauma support, including Blue Knot Foundation, Lifeline and Beyond Blue.

Board of Inquiry staff adhered to a range of relevant protocols when handling information or responding to requests, including referral protocols with the contracted counselling service and Victoria Police, in addition to meeting other legislative obligations relating to privacy and confidentiality.

Healing spaces

The Board of Inquiry recognised the importance of conducting its work with victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members during private sessions, public hearings and roundtables in spaces that promoted healing and that were physically and culturally safe.

When choosing a suitable space in which to conduct this work, the Board of Inquiry considered the following accessibility and safety features,14 among others:

- clear and wide pathways to entrances and exits

- welcoming language used on signage

- wheelchair access via lift

- an abundance of natural light

- adjustable lighting and sound, to create a calmer sensory experience

- the ability to move chairs in the public gallery, to allow people to sit where they felt most comfortable during hearings

- rooms with the ability to webstream, for people who wished to watch the public hearings outside of the hearing room

- breakout spaces and private rooms, so that victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members could have their own comfortable space to meet with support people or a counsellor

- the ability to change the physical hearing space for public hearings, including to ensure the hearing space felt less intimidating for victim-survivors.

Staff were available to welcome participants and other attendees into the space and provide assistance or guidance where appropriate. Staff also monitored the behaviour of others who may be perceived as intrusive or harassing.

The Yoorrook Justice Commission in Collingwood, Victoria is a dedicated space that has been purpose-built to be trauma-informed and culturally safe. The Board of Inquiry was permitted to use the space for private sessions, public hearings and some roundtables. One victim-survivor who spoke to the Board of Inquiry described the Yoorrook facilities as a ‘perfect choice’ of venue.15

The Board of Inquiry extends its thanks to the Yoorrook Justice Commission for its generosity in sharing this beautiful space, which promotes truth-telling and healing.

Engagement and awareness-raising

It was important to raise awareness of the Board of Inquiry’s work to ensure that people with relevant information who wished to participate in the inquiry could do so. Being open, accessible and engaging closely with affected people and communities was a priority for the Board of Inquiry. This section describes the strategies the Board of Inquiry used to maximise engagement with its work.

Engagement with the community

The Board of Inquiry invested in community engagement processes and leveraged key stakeholder networks and traditional media to raise awareness of its work, inform the community of its progress and gather as much information as possible within a short period.

To enable this engagement, the Board of Inquiry developed a comprehensive engagement strategy. During the establishment phase of the inquiry, key stakeholder groups were identified and mapped, and engagement practices were adopted that facilitated two-way information sharing and communication, wherever appropriate.

The strategy was refined over time, allowing the Board of Inquiry to respond to new information it received in a timely, transparent and accessible way. Aspects of the strategy were tested with victim-survivor advocates at various points of the inquiry to ensure they were trauma-sensitive and would meet community needs and expectations.

Part of the engagement strategy was reaching out to communities. The primary objective of community engagement was to raise awareness of the Board of Inquiry’s work, including helping the community understand its purpose, scope and proposed ways of working. The engagement was designed to maximise opportunities for the Board of Inquiry to hear directly from community members about any concerns or suggestions that might inform and improve its approach as it progressed, and to answer any questions. In developing its community engagement, the Board of Inquiry also considered how to reach particular groups it wanted to hear from, by ensuring people felt encouraged and supported to participate. The Board of Inquiry considered community engagement particularly important because it was aware some victim-survivors were not able to contact it by email or telephone, or did not feel comfortable doing so.

Community drop-in sessions

The Board of Inquiry learned that many victim-survivors and secondary victims still live in Beaumaris and the surrounding areas in which they attended school. As a result, community drop-in sessions were planned in locations that would be convenient, namely:

- Sandringham Library, City of Bayside (8 October 2023)

- Hills Hub, Cardinia Shire (12 October 2023)

- Bunjil Place, City of Casey (19 October 2023).

The Chair of the Board of Inquiry was present at all three sessions. Appropriately trained Board of Inquiry support staff were also on hand to support anyone who may have been feeling anxious or distressed and to facilitate referrals to external support services.

A range of people attended the session at the Sandringham Library, with many curious about the Board of Inquiry’s work. Most discussions were exploratory, with people taking information away to reflect on. Several registrations for private sessions were made as a result of these drop-in sessions. Consistent with the relative informality of these sessions and to maintain confidentiality, attendance records for these sessions were not kept. No-one attended the Hills Hub or Bunjil Place sessions.

Telephone line and dedicated email

Members of the public were encouraged to call or email the Board of Inquiry with any questions, concerns or information they may have. The Board of Inquiry established a dedicated email address to receive information and had a telephone line operating during standard business hours throughout the inquiry. These channels were managed by skilled and highly trained staff who were equipped to respond in a timely, professional and empathetic way. More detail on information received through these channels is provided in the next section.

Communications about the Board of Inquiry’s work

The Board of Inquiry website was designed to be accessible and easy to use and was regularly updated. It was an important channel through which the Board of Inquiry could share information and members of the public could engage with the inquiry’s work in a way that suited them. For example, victim-survivors who could not attend the public hearings or did not feel comfortable doing so could watch a video stream of the public hearings on the website. People could also subscribe to an email newsletter that intermittently shared information on the Board of Inquiry’s progress.

Social media also played an important role in disseminating information about the inquiry. Stakeholders and engaged community members regularly shared information about the Board of Inquiry on social media, which helped make the inquiry more visible to a wider group of victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members. City of Bayside was supportive of the Board of Inquiry’s objectives and shared information about it with local community health services, sporting clubs, Men’s Sheds, faith-based and other organisations, and these organisations in turn shared information on their own social media platforms.

Engagement with the media

There was strong media interest in the experiences of victim-survivors and in the Board of Inquiry’s work. While media reporting is an important way to increase awareness and understanding of child sexual abuse, it is important that such reporting is grounded in an understanding of the nature and dynamics of child sexual abuse, and that reporting is done with sensitivity and care.

The Board of Inquiry developed media guidelines, which were issued under section 63(1) of the Inquiries Act and launched at the Board of Inquiry’s initial media conference. These guidelines were available on the Board of Inquiry’s website and provided media organisations with direction on how to uphold the integrity of the Board of Inquiry’s proceedings; in particular, the guidelines provided direction in complying with Restricted Publication Orders made by the Chair. Media organisations were also encouraged to adhere to the national guidance for reporting on child sexual abuse, which is designed to support the media to raise community awareness of child sexual abuse, reduce the stigma experienced by victim-survivors and empower victim-survivors when they share their personal experiences.16

The Board of Inquiry developed a productive working relationship with media organisations throughout the inquiry. Adopting a proactive approach with the media was an important way for the Board of Inquiry to reflect its values of openness and transparency. It also helped ensure that media reporting was accurate and mindful of potential legal and other risks to victim-survivors’ interests.

Information that guided and informed the Board of Inquiry

The Board of Inquiry relied on a range of processes to gather information it needed to do its work. This included seeking documents from state government agencies and other bodies; encouraging members of the public to provide information; inviting submissions from individuals and organisations; conducting private sessions, public hearings, roundtables, targeted consultations and research. This section describes the level and types of information received from these sources.

Notices to Produce and requests for information

The Board of Inquiry issued a total of 15 Notices to Produce to the Victorian Department of Education, Victorian Department of Justice and Community Safety, Victorian Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, and Victoria Police. Notices to Produce are issued under the Inquiries Act and impose legal requirements on government agencies to provided requested information.17 The Board of Inquiry received more than 600 documents in response to Notices to Produce, which informed its public hearings, its ongoing work outside of hearings and, ultimately, the content of this report.

Information was also requested from the Director of Public Prosecutions and Victorian courts, which was shared with the Board of Inquiry on a voluntary basis.

The Board of Inquiry extends its gratitude to all of these organisations for their assistance and cooperation.

Information received from the community

Around 120 victim-survivors, secondary victims, affected community members and other stakeholders shared their experiences with the Board of Inquiry, with approximately 40 making contact specifically to provide information and intelligence.

Of the approximately 120 contacts:

- 68 were victim-survivors

- 11 were secondary victims

- 25 were affected community members. This included current and former teachers at Beaumaris Primary School and other Victorian government schools, former neighbours and acquaintances of alleged perpetrators, local residents of the Beaumaris community, the surrounding areas and former students at other Victorian government schools.

Information provided by people was vital to informing lines of investigation and requests for documents. These contacts also gave Board of Inquiry staff opportunities to invite individuals to participate further or to connect them with support they may need.

Board of Inquiry staff carefully considered all information provided, including information that was ultimately found to be outside the inquiry’s scope.

Submissions

On 7 September 2023, the Board of Inquiry invited submissions from individuals or organisations who had relevant information or expertise to share. The call for submissions was published on the Board of Inquiry’s website and people were encouraged to contact Board of Inquiry staff if they needed any assistance. The Board of Inquiry welcomed submissions in any format, including online, via mail, or in audio or audio-visual formats, and of any length. All people making a submission were prompted to elect how they wished to have their information treated, with the assurance that they could change their preference at any time. The Board of Inquiry specifically sought submissions from victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members.

The submission process was initially open from 7 September 2023 to 31 October 2023, but the Board of Inquiry continued to accept submissions from victim-survivors and secondary victims until 15 December 2023, the same date the private sessions concluded. The Board of Inquiry extended the deadline in acknowledgement that, for some individuals, taking part within the original timeframe may have been difficult and may have caused distress.

As described above, the Board of Inquiry did not dictate the format a submission could take and was open to receiving submissions in writing, audio, image or video formats. People could ask Board of Inquiry staff for help in preparing a submission and would be supported to do so. Many organisations also provided submissions to the Board of Inquiry.

The Board of Inquiry published a guide for individuals making a submission relating to experiences of child sexual abuse. This included some suggested questions for people to consider responding to — the list of questions is included in Appendix F, Submissions(opens in a new window). Participants were also invited to share their thoughts on ways to support healing and their experiences with support services. Organisations were encouraged to outline best-practice, evidence-based approaches to providing effective support services for victim-survivors of child sexual abuse. Further information about submissions can be found in Appendix F.(opens in a new window) As with information provided in private sessions, people or organisations making submissions could elect for their information to be public, anonymous or confidential and change their mind at any time.

All submissions, including those not directly referred to in this report, were closely read and considered by the Board of Inquiry. Where appropriate, counsellors reviewed the material to ensure there were no immediate concerns for an author’s wellbeing. If any concerns were identified, Board of Inquiry staff contacted the author offering them an opportunity to speak confidentially with a counsellor.

The Board of Inquiry made careful decisions about which submissions to publish on its website. Some submissions were not published, whether in whole or in part, for legal reasons (including to comply with a non-publication order), for privacy reasons or because the author requested that the submission not be published.

The Board of Inquiry received 52 submissions from victim-survivors, secondary victims, affected community members, service providers, researchers and experts, non-government organisations and law firms. Of these, 41 submissions were determined to be in scope, including 34 from individuals and seven from organisations.

The Board of Inquiry is grateful for the time and effort put into all the submissions it received.

Private sessions

Private sessions provided a way for victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members to speak directly with the Board of Inquiry and share deeply personal experiences in a safe, private and trauma-informed environment. The purpose of a private session was not to receive evidence on oath or affirmation, or test a victim-survivor’s account of their experiences. All private sessions were conducted at the Yoorrook Justice Commission, with the Chair or Counsel Assisting hosting in person or via video conference. Private sessions generally ran for one hour.

Before a private session, participants were provided with an information sheet titled ‘A guide to your private session’, which outlined what the person could expect on the day, answered frequently asked questions and provided practical information on transport and parking. This guide is in Appendix E(opens in a new window).

Participants could choose how to use the time in their private session and opt to bring a support person or lawyer with them if they wished. In private sessions, people described experiences of child sexual abuse, responses to previous disclosures, the impacts of their experience of child sexual abuse or experiences engaging with services or the justice system. Some also brought documents to their private session, such as police statements, letters, school reports or photographs.

A counsellor was present to support participants before, during and after their private session, with most participants choosing to debrief after their session concluded (how the participant support and care model applied to participants in private sessions is described earlier in this Chapter). Where appropriate, a second private session was conducted.

Participants were asked to consent to have the audio of their private session recorded for the Board of Inquiry’s reference, but could opt out of the recording if they preferred. A Board of Inquiry staff member was also present during private sessions to take written notes of the discussion. As previously discussed, individuals could indicate whether they would like the information they provided through their private session to be treated as public, anonymous or confidential. Where permitted to do so, the Board of Inquiry has included quotes from private sessions in this report, relying on a combination of the notes and audio recordings.

Over the course of the inquiry, 36 people shared their experiences through private sessions. The following 14 individuals, including victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members, wished to share their names publicly:

- Ingrid Carlsen

- Tim Courtney

- Glen Fearnett

- Bryce Gardiner

- Michelle Gilbey

- Grant Holland

- James Macbeth

- Ross McGarvie

- Lindy McManus

- Cheryl Myles

- Rod Owen

- Michael Stretton

- Neil Turton-Lane

- Karen Walker.

It should be noted that it was not always possible or appropriate (including for legal reasons) to link a particular piece of information or attribute a quote to a named individual.

A further 18 individuals sought to share their experiences anonymously. This meant that the person’s information could be used in public hearings or this report, but without any identifying information.

Four individuals sought to share their experiences on a confidential basis, meaning that the information they shared would inform the Board of Inquiry’s work, but it would not be referenced in any way in the inquiry’s work.

The Board of Inquiry felt privileged to receive the trust of private session participants, who showed enormous strength and openness in sharing some deeply painful and traumatic experiences.

Public hearings

The Board of Inquiry held public hearings over seven days between late October 2023 and late November 2023. Hearings were conducted across three phases exploring the following topics:

- Phase One: Experience (23–24 October 2023)

- Phase Two: Accountability (15–17 November 2023)

- Phase Three: Support services and healing (23–24 November 2023).

The complete hearing schedule and list of witness statements can be found in Appendix G, Information about public hearings(opens in a new window).

A range of people were invited to participate in the public hearings in various ways. Some people provided witness statements without giving oral evidence. Some people gave oral evidence, whether they had provided a witness statement or not. For others, an account of their experiences (described as a ‘narrative’) was read out in the hearing by Counsel Assisting or formed part of Counsel Assisting’s address to the Chair. Participants included victim-survivors and secondary victims, relevant experts and representatives from advocacy organisations. Representatives from relevant government agencies, including the Department of Education, prepared witness statements and in some cases were also called to give evidence.

Evidence contained in witness statements has been quoted and relied upon in this report. A list of all individuals who provided witness statements and narratives is in Appendix G(opens in a new window).

As part of fulfilling its objective to create a public record of victim-survivors’ experiences, it was essential that the Board of Inquiry and the wider community heard publicly from victim-survivors about their lived experiences. However, it was equally important that the process for doing so respected victim-survivors’ wellbeing, safety and privacy.

Accordingly, the Board of Inquiry carefully considered how the experiences of victim-survivors and secondary victims could form part of the public hearings. Various methods were chosen. One victim-survivor shared their lived experience and testimony publicly, while another witness chose to give evidence using a pseudonym in a closed hearing, meaning only those in the hearing room could see them give their evidence. In addition, victim-survivors and secondary victims were able to have their stories shared through Counsel Assisting. This enabled experiences to be shared without the victim-survivor needing to formally participate in the hearings as a witness. Where anonymity was sought or required for legal reasons, pseudonyms were used.

In line with the Inquiries Act, the Chair of the Board of Inquiry presided over the hearings. The role of the Chair was to listen and assess evidence. Counsel Assisting held primary responsibility for presenting evidence and questioning witnesses, although at times the Chair would also ask witnesses questions. Counsel Assisting adopted a trauma-informed approach when eliciting information from victim-survivors, who were prepared and guided by counsellors and Board of Inquiry staff about what to expect when giving evidence in the lead up to hearings. Questions were respectful of boundaries defined by witnesses who were sharing personal experiences and witnesses always had the option to take breaks during proceedings, if needed. A trauma-informed approach was also adopted for those victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members whose narratives Counsel Assisting read out as part of the public hearings.

Throughout the public hearings, the Board of Inquiry remained committed to transparency and sharing as much information as possible with the public. However, the Board of Inquiry issued 10 Restricted Publication Orders under section 73(2) of the Inquiries Act that limited the public sharing of information that could identify victim-survivors and alleged perpetrators. These were issued for one of the following reasons:

- To protect the identity of victim-survivors, secondary victims, and community members who gave evidence (or had their experience read out by Counsel Assisting), who did not want to be publicly identified (or could not be for legal reasons).

- Where relevant and appropriate, to create a pseudonym for alleged perpetrators so as to not interfere with current or future civil or criminal proceedings that may be pursued or underway.

Where needed in order to comply with these orders, transcripts and witness statements were redacted, and to avoid any inadvertent breaches of these orders being broadcast, a 10-minute delay was placed on the webstream.

Members of the public and media were invited to attend hearings in person or watch the webstream online, which was available each hearing day. Daily hearing lists, transcripts, some witness statements, video recordings of the hearings and Restricted Publication Orders were published on the Board of Inquiry’s website. The Board of Inquiry has quoted evidence from publicly released transcripts of public hearings throughout this report.

The Board of Inquiry also developed ‘A guide to public hearings for victim-survivor participants’, which was designed to prepare victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members attending a public hearing. This guide was designed to reduce stress on the day by clearly describing what to expect during and after hearings, as well as providing important information on the location of the hearings, and on transport and parking. The guide to public hearings is in Appendix G.(opens in a new window) A range of counselling support services were provided to witnesses and other attendees who may have been affected by the public hearings. A First Aider and First Responder from St John Ambulance Australia and a security professional were onsite for every public hearing to assist with safety and wellbeing.

There was significant media interest in the Board of Inquiry’s public hearings. The Board of Inquiry supported victim-survivors who wished to share their experiences with the media by ensuring they felt safe and comfortable to do so.

Roundtables

Between 29 November 2023 and 14 December 2023, the Chair of the Board of Inquiry hosted five roundtables to gather further information. These were:

- Roundtable 1 (29 November 2023): Support Services

- Roundtable 2 (29 November 2023): Healing

- Roundtable 3 (1 December 2023): Lived Experience

- Roundtable 4 (1 December 2023): Support Services

- Roundtable 5 (14 December 2023): Government’s role in provision of services and supporting healing.

The composition of the roundtables varied depending on the subject to be discussed. Overall, participants included victim-survivors and secondary victims, representatives from support and advocacy services, community members with relevant experience, researchers and academics, and government representatives. A full list of roundtable participants can be found in Appendix H, Roundtables(opens in a new window).

The purpose of the roundtables was to provide an opportunity for structured discussions on questions and issues arising from the hearings about the effectiveness of support services and appropriate ways to support healing. Each roundtable was supported by a discussion guide setting out expectations, roundtable etiquette and questions to guide the conversation.

For the roundtables on support services and healing, the Board of Inquiry invited organisations and individuals with expertise and experience in delivering support services and developing healing responses. The Board of Inquiry invited several victim-survivors and secondary victims who had already participated in private sessions to attend the Lived Experience Roundtable to obtain further input from them. A final roundtable was held with representatives from across Victorian government agencies to respond to specific themes and issues that had arisen during the hearings and previous roundtables.

Each roundtable was scheduled for two hours and hosted by either the Board of Inquiry Chair or Chief Executive Officer. Roundtables were held online, in person or through a combination of the two. Consent was sought for roundtable discussions to be audio recorded and in some cases visually recorded to enable records of proceedings to be prepared for the Board of Inquiry’s reference. In order to facilitate open discussion, the Chair or CEO advised participants that while this report may refer to themes or issues discussed at roundtables, it would generally do so without attributing particular statements to individuals. The Chair or CEO also advised participants of the Support Services and Healing Roundtables that the report would only attribute a quote to an individual if that person gave their consent. Participants at the Lived Experience Roundtable were advised that all information in the report would be anonymised, even where quotes were used (which would only be done with permission).

Roundtables built on the evidence heard at public hearings and were a valuable mechanism enabling people with a range of expertise and perspectives to contribute to the Board of Inquiry’s work. They also offered another opportunity for victim-survivors and secondary victims to participate in this work.

Targeted consultations and research

The Board of Inquiry also engaged directly with several individuals and organisations through a series of targeted consultation meetings. There were a range of reasons for these consultations — for example, to help identify potential witnesses, to seek specific information on areas of expertise or to test ideas. Further information about people and organisations consulted is in Appendix I, Consultations(opens in a new window). Concurrently, the Board of Inquiry undertook independent research and literature reviews to help inform its work.

Procedural fairness

In accordance with the Inquiries Act and with its other legal obligations, the Board of Inquiry designed and conducted its inquiry in such a way that it afforded procedural fairness to those entitled to it.

From the outset, the Board of Inquiry recognised it would likely hear allegations or receive information about persons that would require it to consider its procedural fairness obligations in relation to those persons. The Board of Inquiry developed principles for deciding how it would manage any such allegations or information. This involved deciding whether and how the Board of Inquiry might seek to explore allegations or information, as well as when and why it might publicly identify any person as a relevant employee.

The Board of Inquiry sought to engage with the three alleged perpetrators who were still alive, including through any lawyers who were retained to assist them. The Board of Inquiry explained its approach to the public hearings, including the use of Restricted Publication Orders, pseudonyms and de-identification, and advised how the alleged perpetrators and their legal representatives could access information about the hearings. In each case, the Board of Inquiry foreshadowed that it would provide draft content of this report that was adverse to them and provide them with an opportunity to provide a response to it. The Board of Inquiry also provided an open invitation for the individual to engage with the Board of Inquiry at an earlier stage if they wished to do so (that is, prior to receiving the draft report content). Only one alleged perpetrator did so, by writing to the Board of Inquiry about allegations and information in relation to them that was covered during the public hearings. Subsequently, one of these three alleged perpetrators died.

Consistent with its earlier communication, the Board of Inquiry re-engaged with the two alleged perpetrators who were still alive in relation to draft content of the report that was adverse to them, including the victim-survivor and secondary victim narratives and other specific allegations or commentary in relation to them. These individuals provided responses to the Board of Inquiry, which have been carefully considered and are addressed later in this report. More detail about the procedural fairness process in relation to each alleged perpetrator is set out in Chapter 11, The alleged perpetrators(opens in a new window).

The Board of Inquiry’s procedural fairness process also involved engaging with the State of Victoria, including the Department of Education, Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, Department of Justice and Community Safety and Victoria Police, in relation to any adverse material in relation to these agencies. As a consequence, the Board of Inquiry provided the State with certain draft chapters that contained specific findings or adverse comments for the State to review. The State provided submissions in relation to these draft chapters and the Board of Inquiry took these into account before it finalised the report. The State was not provided with any other draft chapters or content prior to finalising the report.

In terms of procedural fairness responses, one relevant employee disagreed with the Board of Inquiry using the phrase ‘victim-survivor’ in the report, on the basis it could be understood as assuming the victim-survivor experiences shared with the Board of Inquiry and included in the report are true. He requested that the term ‘alleged victim-survivor’ be adopted in all instances where there has been no conviction. Despite this suggestion, the Board of Inquiry has used the term ‘victim-survivor’. The Order in Council establishing the Board of Inquiry uses this language in the inquiry’s Terms of Reference. Further, ‘victim-survivor’ is widely accepted terminology and was the way many people identified themselves to the Board of Inquiry. The use of this term does not, and is not intended to, indicate that the Board of Inquiry has made any findings of fact in relation to the experiences of victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members.

The Board of Inquiry was also conscious of the risks involved in publicly identifying relevant employees. If the Board of Inquiry decided, having regard to all the circumstances, that it was not appropriate to publicly identify a relevant employee, the Board of Inquiry made Restricted Publication Orders, used pseudonyms and otherwise de-identified and protected information in relation to the relevant employee.

Lessons learned

Each inquiry aims to build on previous inquiries, and in doing so, benefits greatly from what these inquiries learned about what worked well and what could be improved. The Board of Inquiry is proud of many elements of its work, particularly its participant care and support model, which aimed to offer personalised support to participants with an experience of trauma. However, the Board of Inquiry also recognises the importance of reflecting on areas of potential improvement. It is in this spirit that some key reflections from the Board of Inquiry are presented here.

While time and resources did not allow for the Board of Inquiry to conduct a full evaluation of the participant care and support model, participants and stakeholders were encouraged to provide feedback at any point about the Board of Inquiry’s work. Some of the feedback received and insights gained about the model are summarised below, along with some informal reflections on the operation of the inquiry itself.

Reflections on the participant care and support model

As noted throughout this Chapter, the Board of Inquiry deliberately embraced a trauma-informed approach when fulfilling its objectives and addressing its Terms of Reference. In doing so, it built on the lessons learned from some previous inquiries. Some of the approaches to communication, care and support adopted were new in the context of Victorian inquiries and the Board of Inquiry wanted to understand how participants experienced them. In some part due to having a small team, the Board of Inquiry could foster a supportive culture and continuously learn and improve processes and practices in order to meet the needs and wishes of participants.

Feedback from participants, provided both formally and informally, reinforces the value of inquiries such as the Board of Inquiry engaging with the community openly and designing and implementing a comprehensive model of care and support to encourage participation. These initiatives, in and of themselves, played a crucial role in victim-survivors’ healing journeys. Victim-survivors who engaged with the Board of Inquiry frequently provided feedback about their experiences, with many noting the importance and value of a participant care and support model that met their diverse needs, was emotionally validating and recognised that support methods can be delivered through formal and informal approaches. The majority of feedback received was informal but was overwhelmingly positive, with people reporting that they were met with compassion, empathy and careful consideration of their needs.

Some victim-survivors reflected that it was rewarding to be part of a person-centred care model that was effective for both the individual and the family unit. For many, the care and support they were provided contributed to greater emotional self-control, increased interpersonal trust and feelings of empowerment, reduced self-blame, and improved attachment to their loved ones. The Board of Inquiry also acknowledges how emotionally difficult it was for many victim-survivors to engage with the inquiry’s work, given the subject matter. The Board of Inquiry hopes that its approach made that difficult journey a supported one.

Reflections on how the inquiry operated

Areas of improvement identified primarily related to the short, 12-week timeframe for participation in a private session. Some people, particularly those disclosing their experiences for the first time, felt this did not provide them sufficient time to prepare psychologically. Given the short duration of the Board of Inquiry, it was inevitable that some participants would feel that processes were rushed. For future inquiries dealing with similarly sensitive subject matter (where some participants will need a good deal of time to decide whether to even engage with the inquiry), longer overall timeframes for the inquiry should be considered.

A key feature of the participant care and support model was that victim-survivors could choose whether to engage with counsellors. For many victim-survivors, their initial response was to not engage. However, they often changed their mind after participating in a private session. Many people reported their experience participating in a private session as one that, while difficult, contributed positively to their healing, and that this prompted them to continue on a therapeutic journey. For some, participating in a private session caused quite significant emotional distress and they recognised that they needed counselling support. The flexibility of the model enabled victim-survivors to safely request counselling, and decide how it was delivered.

Some people requested counselling support for immediate family members who were not formally participating in the inquiry, such as partners, siblings and children. The Board of Inquiry understood the impact that an individual’s participation was likely to have on their families, friends, loved ones and supporters and made suitable accommodations to ensure that anyone affected by the inquiry could access counselling support. Participants valued the personalisation of care and support, with many noting informally that it increased closeness in their relationships.

The Board of Inquiry is proud of the model of support it developed and hopes that it informs future inquiries involving participants who have experienced trauma, recognising the inherent power of an inquiry process to offer acknowledgement and validation of experiences and contribute to recovery.

Chapter 1 Endnotes

- ‘Inquiry into Historical Abuse at Beaumaris Primary School’, Inquiry into Historical Abuse at Beaumaris Primary School (Web Page, updated 7 September 2023) <https://www.vic.gov.au/inquiry-historical-abuse-beaumaris-primary-school>(opens in a new window).

- ‘Vic Premier Andrews Holds Joint News Conference’ (Nine News, 28 June 2023).

- The Hon Daniel Andrews MP, ‘Inquiry into Historical Abuse at Beaumaris Primary’ (Media Release, 28 June 2023) <https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/inquiry-historical-abuse-beaumaris-primary>(opens in a new window).

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 2(a).

- ‘What is Truth-telling?’, ANTAR (Web Page, 21 November 2023) <https://antar.org.au/issues/truth-telling/what-is-truth-telling>(opens in a new window).

- Media conference with the Hon Daniel Andrews, 28 June 2023.

- Claire Barker, Stephanie Ford, Rebekah Eglinton, Sally Quail and Daniel Taggart, ‘The Truth Project Paper One — How Did Victims and Survivors Experience Participation? Addressing Epistemic Relational Inequality in the Field of Child Sexual Abuse’ (2023) Front Psychiatry 1, 2.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach, July 2014 <https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf>(opens in a new window).

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 3(2)(b) and (c).

- Ravi Dykema, ‘“Don’t Talk to Me Now, I’m Scanning for Danger”: How Your Nervous System Sabotages Your Ability to Relate — An Interview with Stephen Porges about His Polyvagal Theory’ (March/April 2006) Nexus 30, 31–2.

- The Hon Daniel Andrews MP, ‘Inquiry into Historical Abuse at Beaumaris Primary’ (Media Release, 28 June 2023) <https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/inquiry-historical-abuse-beaumaris-primary>(opens in a new window).

- ‘Vic Premier Andrews Holds Joint News Conference’ (Nine News, 28 June 2023).

- George Tate, ‘Therapeutic Process: Definitions and Theory’, in Strategy of Therapy (Springer, 1967) 40

<https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-40411-9_3>(opens in a new window). - C Clark, CC Classen, A Fourt and M Shetty, ‘Understanding Trauma and Trauma-informed Care: The Basics’, in Treating the Trauma Survivor: An Essential Guide to Trauma-informed Care (1st ed) (Routledge, 2015).

- Private session 30.

- Commonwealth Government (National Office for Child Safety) and University of Canberra, ‘Reporting on Child Sexual Abuse: Guidance for Media’ (2003) <https://www.childsafety.gov.au/system/files/2023-07/reporting-on-child-sexual-abuse-guidance-for-media.pdf>(opens in a new window).

- Inquiries Act 2014 (Vic) pt 3 div 4.

Updated