Introduction

Governments initiate inquiries for various reasons, including to investigate and explain complex events or intractable problems. At the time of establishment of an inquiry, it can be difficult to predict the nature and type of information that the inquiry may need to carry out its work, and to anticipate what other information might be uncovered during its course. It is important for terms of reference to be specific enough to give the inquiry a clear purpose and mandate that it can follow, without constraining it from considering all sources of information that may turn out to be relevant to the issues it has been asked to investigate. The Board of Inquiry acknowledges that it is difficult to strike this balance.

As foreshadowed above, all inquiries must confront the limits imposed by their terms of reference, and the present inquiry is no exception. In some instances, legal requirements will dictate hard limits. However, even the most specific terms of reference generally require a degree of interpretation, and this invites difficult decisions. Such decisions are informed by a range of factors, including both public interest and practical considerations (for example, time and available resources). They require a balancing of the ambition to do as much as possible within the scope of the terms of reference with the need to deliver public benefit within the timeframe chosen by government.

This Chapter describes how the Board of Inquiry interpreted its Terms of Reference and the decisions it made in the course of determining whether information was within scope. It also details some of the challenges the Board of Inquiry faced in respect of its Terms of Reference, particularly with regard to the identification and gathering of information, and then the setting of thresholds for investigating matters that it considered relevant.

Terms of Reference

Clause 3 of the Order in Council sets out the Terms of Reference for the Board of Inquiry.1 These were ‘to inquire into, report on and make any recommendations considered appropriate in relation to’ the following:

- The experiences of victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse who were abused by a relevant employee at Beaumaris Primary School during the 1960s and/or 1970s;

- The experiences of victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse who were abused by a relevant employee in any other government school;

- The response of the Department of Education in relation to the historical child sexual abuse described in clauses (3)(a) and (b) above, including the Department of Education and its officers’ state of knowledge and any actions it took or failed to take at or around the time of the abuse;

- Appropriate ways to support healing for affected victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected communities including, for example, the form of a formal apology, memorialisation or other activities;

- Having regard to other inquiries and reforms that have taken place since the historical child sexual abuse occurred, whether there are effective support services for victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools;

- Any other matters related to these Terms of Reference necessary to satisfactorily inquire into or address the Terms of Reference.2

The Terms of Reference directed the Board of Inquiry not to inquire into:

- The response of the State (including the Department of Education and its staff) to any complaints, legal proceedings or legal claims in relation to incidents of historical child sexual abuse in a government school, except insofar as the inquiry may establish a factual record of the state of knowledge of the Department of Education and its staff and the actions taken or not taken by the Department and its staff at or around the time of the historical child sexual abuse ...

- Compensation and/or redress arrangements, including settlement of any civil claims, for victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse.3

A copy of the Order in Council is in Appendix A(opens in a new window).

Assessing whether information relating to experiences of child sexual abuse was within scope

The Board of Inquiry received a range of information describing experiences of child sexual abuse that fell outside the scope of the Terms of Reference. While the Board of Inquiry was not able to inquire into any information that was outside the scope of the Terms of Reference, it did carefully consider whether such information was within scope. Sometimes, further enquiries were required to assist the Board of Inquiry to understand whether the information received was within the scope of the Terms or Reference or not. If the Board of Inquiry determined the information was within scope, it then considered whether any follow-up action was required. Furthermore, as noted in Chapter 1, Establishment and approach(opens in a new window), the Board of Inquiry offered appropriate support and private sessions to people who provided information about their experiences of child sexual abuse, regardless of whether their experiences came within the Board of Inquiry’s Terms of Reference.

Sometimes it was very clear that information fell outside the Terms of Reference. Examples include information that:

- did not involve child sexual abuse (for example, information about physical abuse only)

- related to child sexual abuse in settings that had no connection to a school or a school employee (for example, child sexual abuse perpetrated by a stranger at the beach or by a family member)

- related to child sexual abuse that occurred outside the relevant period identified in the Terms of Reference, being 1 January 1960 to 31 December 1999 (the relevant period is discussed further in the next section)

- related to child sexual abuse that occurred at a non-government school, such as a private or religious school

- related to child sexual abuse that occurred outside Victoria.

Sometimes it was more difficult to determine whether information fell outside the Terms of Reference. In such cases, the Board of Inquiry attempted to gather further information. This generally occurred where:

- it was difficult to determine the identity of an alleged perpetrator or confirm the school (or schools) where they worked and when

- there was information that suggested the possibility that an alleged perpetrator may be a relevant employee, but further information was needed to confirm this (for example, to confirm they had worked, and were alleged to have perpetrated child sexual abuse, at Beaumaris Primary School in the 1960s or 1970s)

- the child sexual abuse was alleged to have occurred at a government school, but it was unclear whether it was alleged to have been perpetrated by a relevant employee and therefore whether that school was within scope

- the child sexual abuse occurred outside a government school premises, but it was necessary to consider if a government school, or its activities, had ‘created, facilitated, increased, or in any way contributed to … the risk of child sexual abuse’.4

These issues, and how the Board of Inquiry ultimately interpreted key terms in its Terms of Reference, are explained further in the next section.

The Board of Inquiry continued to seek and receive information throughout the life of the inquiry. Whenever it received new information, the Board of Inquiry actively considered whether this new information required a revisiting of other information and initial decisions it might have made about whether such other information was out of scope.

How the Board of Inquiry interpreted its Terms of Reference

This section describes the key decisions the Board of Inquiry made about the scope of its work under the Terms of Reference. Interpreting and applying the Terms of Reference was complex, but it is important to understand how the Board of Inquiry approached this task, as it determined what information and issues are considered in this report.

In addition, this section describes the practical effect of the Terms of Reference, including decisions made by the Board of Inquiry where it was required to interpret the Terms of Reference or apply them to information received. A key challenge was the narrow definition of ‘relevant employee’ and the flow-on effects this definition had on the ability of the Board of Inquiry to consider information about other schools or alleged perpetrators. Despite the wide-ranging information received, the Board of Inquiry determined that, on the information available to it, only six people satisfied the definition of relevant employee. This in turn determined the schools and other settings in which the Board of Inquiry could consider allegations of child sexual abuse, and excluded other schools or alleged perpetrators who might otherwise have been seen as relevant.

This section also outlines how the Board of Inquiry treated certain other information, including information received about the disappearance of Eloise Worledge, a student at Beaumaris Primary School in the 1970s.

Defining the relevant period

The relevant time period, for the purposes of the Board of Inquiry’s work, was between 1 January 1960 and 31 December 1999. However, as will be explained, a question arose as to whether a narrower time period (the 1960s and the 1970s) was applicable to Beaumaris Primary School, as opposed to other government schools.

This question reflects two aspects of the Terms of Reference. The Terms of Reference defined a ‘relevant employee’ as ‘a teacher or other government school employee or contractor who sexually abused a student at Beaumaris Primary School during the 1960s or 1970s’.5 This meant that 1 January 1960 was the starting point of the relevant period. By clause 3(b), the Terms of Reference also contemplated consideration of ‘historical child sexual abuse’ perpetrated by these relevant employees at other government schools, defining ‘historical child sexual abuse’ as ‘sexual abuse of a child in a government school by a staff member employed by the Department of Education in a government school, where that abuse occurred on or prior to 31 December 1999’.6 This meant that 31 December 1999 was the end point of the relevant period.

However, the Terms of Reference drew a distinction (in clauses 3(a) and (b)) between child sexual abuse by a relevant employee at Beaumaris Primary School ‘during the 1960s and/or 1970s’ (on the one hand), and child sexual abuse by a relevant employee at any other government school (on the other hand). Because the narrower timeframe (the 1960s and/or 1970s) was only used in respect of child sexual abuse alleged to have occurred at Beaumaris Primary School, the broader timeframe (from 1 January 1960 to 31 December 1999) only applied to child sexual abuse alleged to have occurred at other government schools.

Accordingly, on a strict reading of the Terms of Reference, an allegation of child sexual abuse by a relevant employee at Beaumaris Primary School between 1980 and 1999 would fall outside the Terms of Reference. Given, however, that clause 3(f) of the Terms of Reference contemplated the Board of Inquiry considering ‘[a]ny other matters related to these Terms of Reference necessary to satisfactorily inquire into or address the Terms of Reference’, the Board of Inquiry considered it was within scope to consider any allegation of child sexual abuse by a relevant employee at Beaumaris Primary School between 1 January 1960 and 31 December 1999. It is difficult to see how the objectives of the Board of Inquiry (as set out in the Order in Council) could be met if an allegation against a relevant employee in (say) 1980 could not be inquired into as part of the Board of Inquiry’s work. This was particularly so in light of the fact, as set out in Part C(opens in a new window) of this report, that a relevant employee was employed at Beaumaris Primary School after 31 December 1979.

Determining who was a ‘relevant employee’

The concept of a ‘relevant employee’ was central to the Terms of Reference and shaped the scope of the inquiry. It was defined as follows:

a teacher or other government school employee or contractor who sexually abused a student at Beaumaris Primary School during the 1960s or 1970s.7

A question arose as to the meaning of the language ‘who sexually abused a student’ in the definition. On one view, this could be interpreted to require (to meet the definition) a formal finding that a person had committed sexual abuse against a student; for example, a criminal conviction, a finding in a civil case or a formal disciplinary finding. However, the Board of Inquiry did not adopt this narrow interpretation for the following reasons:

- Such a narrow interpretation would be inconsistent with clause 1(e) of the Order in Council, which refers to relevant employees as ‘allegedly’ harming multiple victim-survivors and ‘allegedly’ perpetrating sexual abuse towards students. Clause 1(e) makes clear that these allegations of child sexual abuse were to be the subject of the Board of Inquiry. Clause 1(e) was not limited to formal findings of child sexual abuse.

- Such a narrow interpretation would also be inconsistent with the language of clause 2(a) of the Order in Council, which refers to establishing a ‘public record of victim-survivors’ experiences’. The language of ‘experiences’ (which is repeated in clauses 3(a) and (b)) is consistent with a focus on what victim-survivors recall and are able to share with the Board of Inquiry, rather than a focus on what has or has not been formally established in a court or disciplinary setting.

- The Board of Inquiry recognises the very real and understandable barriers to disclosure that many victim-survivors confront, and did not want to contribute to the sense of shame or self-blame that some victim-survivors carry for not reporting their child sexual abuse.

- Failures to conduct robust disciplinary investigations or police investigations into allegations of child sexual abuse were likely to have been a feature of institutional responses at that time, and requiring a formal finding of child sexual abuse would limit the ability of the Board of Inquiry to understand the extent of historical child sexual abuse and hold relevant agencies accountable for failures to act.

- Such an interpretation would have likely discouraged people from providing important information on the basis that there was no formal finding against an alleged perpetrator (or they were unsure if there was such a finding).

- Historic record-keeping practices by schools and the Department of Education (Department) may have limited the ability of the Board of Inquiry to confirm the existence of disciplinary findings.

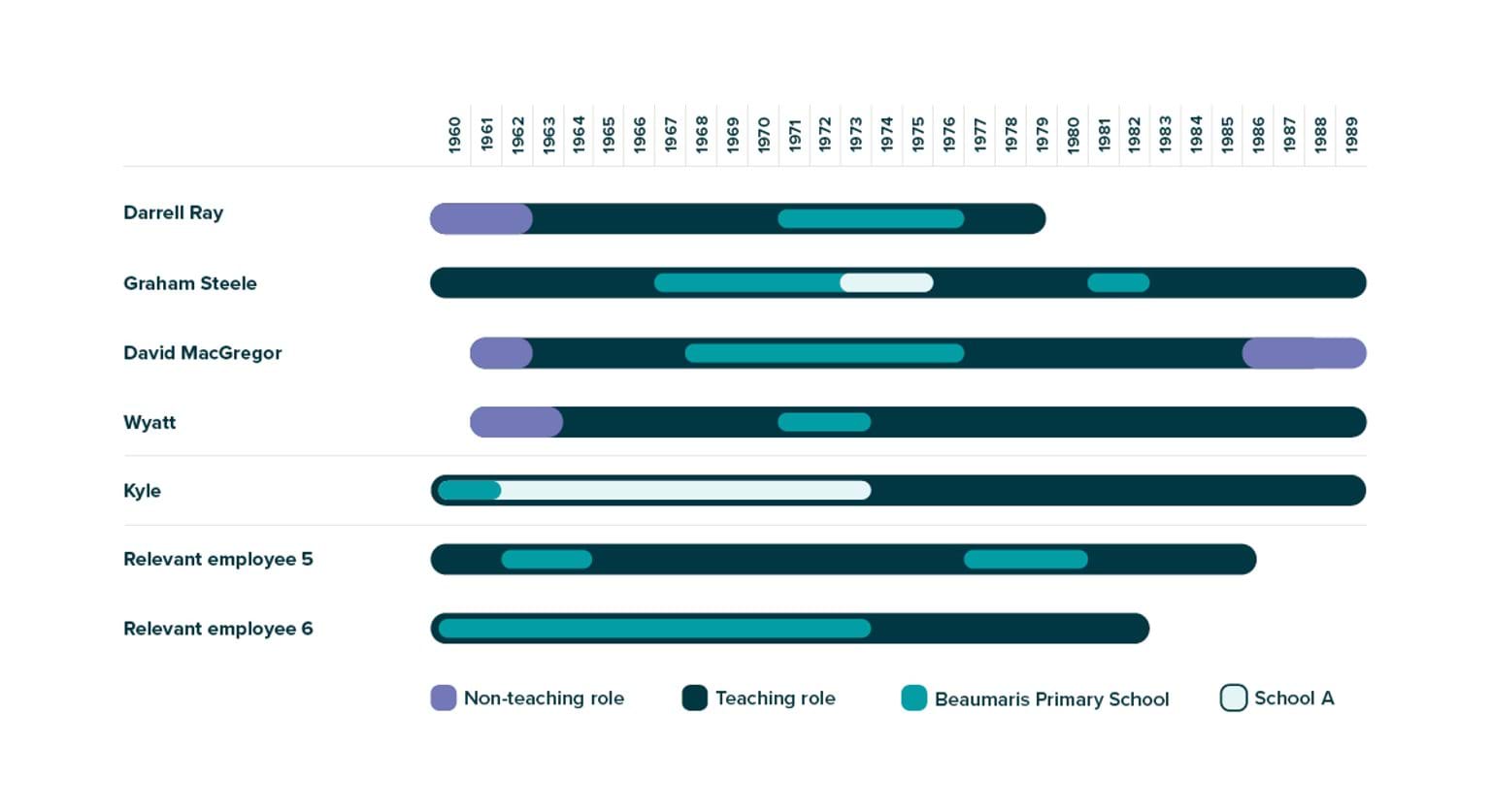

Ultimately, the Board of Inquiry determined that six people satisfied the definition of ‘relevant employee’. The following three relevant employees are named in this report:

- Darrell Vivienne Ray (also known as Darrell Vivian Ray and Ray Cosgriff) born 14 May 1941; died 21 November 2023

- Graham Harold Steele (also known as Grahame Steele) born 3 May 1932; died 2013

- David MacGregor born 8 January 1943.8

A fourth person determined to be a relevant employee cannot be named in order to avoid causing prejudice to current or future criminal or civil proceedings, or otherwise giving rise to other legal issues. Instead, this person is referred to using the pseudonym ‘Wyatt’ in this report.9

The Board of Inquiry also heard allegations from one victim-survivor in relation to two further relevant employees, who are not named in this report. As with the other four relevant employees, the Board of Inquiry sought to investigate these two individuals, including through issuing Notices to Produce to the Department in each case seeking their employment record, information in relation to any allegations of child sexual abuse and any response to or investigation of such allegations, and information in relation to any relevant criminal or civil proceedings.10 The Department responded in each case stating that it had not found records documenting such allegations or any relevant criminal or civil proceedings.11 The Department advised that the personnel files for these two relevant employees did not contain any record of disciplinary action and the Department was unable to locate any disciplinary files.12 The Board of Inquiry’s review of the employment record for each individual did not identify any further relevant information. In the absence of any further allegations or information in relation to these two relevant employees, and taking into account the implications for them if they were named, the Board of Inquiry determined it was not appropriate to publicly identify them. The Board of Inquiry determined that the focus of its investigation would remain on the other four relevant employees in relation to whom it received a considerable amount of information. It is for this reason that these other two relevant employees are not the subject of any further detailed discussion in this report.

More broadly, the Board of Inquiry has been careful not to prejudice any criminal or civil legal proceedings or otherwise create legal issues that may adversely affect those participating in or impacted by the Board of Inquiry’s work. Importantly, it was not the role of the Board of Inquiry to make findings that child sexual abuse did or did not occur. Establishing a public record of victim-survivors’ experiences is not equivalent to (and should not be understood as) making findings of fact about particular events. Accordingly, the Board of Inquiry has not directly investigated allegations of child sexual abuse, beyond confirming basic information relevant to the Terms of Reference. As a result, the Board of Inquiry uses the term ‘alleged perpetrator’ throughout this report, including to describe relevant employees. This is not intended to be interpreted as the Board of Inquiry casting doubt on the recollections of victim-survivors and others; rather, it is intended to make clear the scope of the Board of Inquiry’s role and to safeguard the integrity of legal processes that are underway or may be initiated in the future.

Challenges with the narrow definition of ‘relevant employee’

The definition of ‘relevant employee’ was the gateway for experiences of historical child sexual abuse to be within the scope of the Board of Inquiry. If an alleged perpetrator of child sexual abuse did not meet this specific definition, then information in relation to them could not be considered for the purposes of clauses 3 (a), (b) and (c) of the Terms of Reference. The Terms of Reference were focused on persons (relevant employees) and the government schools where they worked, rather than just on the schools themselves. Accordingly, an allegation of child sexual abuse by a teacher at Mount View Primary School (for example) would only come within the scope of the Terms of Reference if the alleged sexual abuse was perpetrated by a relevant employee.

The practical effect of the definition of ‘relevant employee’ was that the Board of Inquiry could only consider experiences of child sexual abuse if it could first establish with a reasonable level of confidence that the alleged perpetrator had worked at Beaumaris Primary School between 1960 and 1979, and that the alleged perpetrator was the subject of an allegation of child sexual abuse said to have occurred at that school during that period. Once these two limbs were confirmed, experiences of child sexual abuse allegedly perpetrated by that relevant employee at Beaumaris Primary School and other government schools between 1960 and 1999 came within scope.

Because each of the relevant employees worked at government schools other than Beaumaris Primary School between 1960 and 1999, this meant that sometimes critical information received from a source that confirmed an alleged perpetrator was a relevant employee could bring a range of other schools or settings within the scope of the Terms of Reference.

However, this also meant that any allegations about child sexual abuse against a person who was teaching in a government school in the Beaumaris area but was not a relevant employee (because, for example, there was no allegation of child sexual abuse by that person of a student at Beaumaris Primary School) could not be included in this report. While clause 1(e) of the Order in Council makes clear that the Victorian Government’s decision to constitute the Board of Inquiry was made against the background of allegations concerning a cluster of teachers who were allegedly perpetrating child sexual abuse at Beaumaris Primary School (and in relation to allegations of sexual abuse by those same teachers at other government schools), this limitation was a source of frustration for people who approached the inquiry with a genuine belief they would be able to have their experiences form part of the public record.

Due to the definition of ‘relevant employee’, the Board of Inquiry was unable to examine allegations of child sexual abuse in relation to one government school close to Beaumaris Primary School. It was also unable to examine allegations of child sexual abuse in relation to teachers who worked at Beaumaris Primary School and other government schools, but were not the subject of any allegations of child sexual abuse while at Beaumaris Primary School. Further it was unable to examine allegations of child sexual abuse in relation to teachers who worked at a nearby school, but did not work at Beaumaris Primary School. These include allegations relating to one teacher with links to relevant employees, which is illustrated below.

‘KYLE’

The Board of Inquiry received information about allegations of child sexual abuse against a teacher, ‘Kyle’ (a pseudonym), who worked at Beaumaris Primary School in the early 1960s before going on to work at a range of other schools in the area.13

Critically, the Board of Inquiry did not receive any allegations of child sexual abuse against Kyle in relation to his time at Beaumaris Primary School. The Board of Inquiry did, however, receive extensive information alleging that Kyle perpetrated child sexual abuse in a government school context during the relevant period. This included information alleging child sexual abuse by Kyle against nine separate victim-survivors. Eight of these victim-survivors attended the same government school, which was close to Beaumaris Primary School, and the ninth victim-survivor attended a nearby government school. Kyle briefly worked alongside a relevant employee at one of these local government schools for a year (referred to in Diagram 5 as School A). That relevant employee is alleged to have perpetrated child sexual abuse at that school the following year.

As the Board of Inquiry did not receive any allegations of child sexual abuse against Kyle in relation to his time at Beaumaris Primary School, Kyle did not meet the definition of a ‘relevant employee’ and, as a result, the experiences of victim-survivors who reported sexual abuse by Kyle, and the Department’s actions in relation to Kyle, were not within the scope of the Board of Inquiry’s work (except in relation to clause 3(e) of the Terms of Reference, as discussed further below). This is despite the fact that he was alleged to have sexually abused students at other government schools in close geographical proximity to Beaumaris Primary School and had at least one professional connection with a relevant employee the Board of Inquiry was examining.

Kyle was not the only teacher at a government school close to Beaumaris Primary School who was the subject of allegations by persons who came forward to the Board of Inquiry, and yet was determined not to be a relevant employee.

Determining which other government schools were within scope

For a school other than Beaumaris Primary School to be within the scope of the Terms of Reference, it needed to meet the following requirements:

- It must have been a Victorian government school at the relevant time.

- A person meeting the definition of ‘relevant employee’ must have worked there (as part of this definition, they must have worked there as teacher, employee or contractor of the Department).

- The allegations against the relevant employee must be of child sexual abuse occurring on or prior to 31 December 1999 (thereby meeting the definition of ‘historical child sexual abuse’ in the Terms of Reference).

In practice, the effect of these requirements is that the teaching history of Mr Ray, Mr Steele, Mr MacGregor and Wyatt dictated which other government schools came within scope. Essentially, it obliged the Board of Inquiry to follow the careers of these four relevant employees through to 1999. The Board of Inquiry relied on the Department to confirm information about the government schools where each relevant employee worked (including their role and length of service).

The Board of Inquiry is aware that one relevant employee went on to teach at an independent school after ceasing their employment in government schools. Due to the focus of the Terms of Reference on child sexual abuse that took place ‘in a government school’, this independent school was not within the scope of this inquiry.

In October 2023, the Board of Inquiry publicly identified the 24 schools that met all these requirements:

- Aspendale Primary School

- Beaconsfield Upper Primary School

- Beaumaris Primary School

- Belvedere Park Primary School

- Bundalong South Primary School (now closed)

- Bunyip Primary School

- Chelsea Heights Primary School

- Cowes Primary School

- Cranbourne Primary School

- Dandenong North Primary School

- Dandenong West Primary School

- Drouin South Primary School

- Emerald Primary School

- Hampton Primary School

- Kunyung Primary School

- Mirboo Primary School, now Mirboo North Primary School

- Moorabbin (Tucker Road) Primary School, now Tucker Road Bentleigh Primary School

- Moorabbin West Primary School (now closed)

- Mount View Primary School

- Ormond East Primary School, now McKinnon Primary School

- Tarraville Primary School (now closed)

- Tarwin Lower Primary School

- Warragul Primary School

- Warragul Technical School, now Warragul Regional College.14

If a relevant employee is alleged to have perpetrated child sexual abuse at one school, it invites the question of what might have occurred at other schools where they worked. It also invites the question of whether child sexual abuse might have occurred ‘in a government school context’ (discussed in the next section). The Terms of Reference permitted the Board of Inquiry to examine child sexual abuse that allegedly took place at ‘other government schools’ and in a ‘government school context’, but in each case there needed to be a connection to a relevant employee (and, therefore, Beaumaris Primary School).

Accordingly, despite a wide-ranging communications and engagement strategy, most of the information the Board of Inquiry received related to the Beaumaris community and, to a lesser extent, the surrounding areas. In this way, the Board of Inquiry’s work, pursuant to the Terms of Reference, focused on a particular community within a specific period. Even in relation to that community (Beaumaris and the surrounding areas), the Board of Inquiry’s focus was limited to schools where relevant employees taught.

Determining what other settings were within scope

The Terms of Reference define ‘in a government school’ broadly to mean ‘in a government school context’. The definition includes child sexual abuse that:

- happened on the premises of a government school, where activities of that school took place, or in connection with the activities of that school; or

- was engaged in by a relevant employee in circumstances (including circumstances involving settings not directly controlled by the government school) where you consider that the government school had, or its activities had, created, facilitated, increased, or in any way contributed to (whether by act or omission) the risk of child sexual abuse or the circumstances or conditions giving rise to that risk.15

This wide definition of ‘in a government school’ enabled the Board of Inquiry to consider child sexual abuse by relevant employees in settings that went beyond government school facilities or premises. For example, the Board of Inquiry considered the following settings to be within scope on the basis that they were settings where activities of the school took place or were in connection with activities of the school:

- school camps (including Somers School Camp and Berry Creek Camp)

- school sporting excursions.

The Board of Inquiry also considered that other settings came within scope where the fact that the relevant employee was in a position of trust by virtue of their status as a teacher in a government school during the relevant period, and likely held in high regard by the relevant community, would have given rise to a perception that activities involving that person were appropriate and safe for children, at school and beyond. In this context, the relationship between the government school and the relevant employee had contributed to the risk of child sexual abuse. On this basis, the Board of Inquiry considered the following settings connected to relevant employees to be within scope:

- community sporting settings (discussed in more detail below)

- a relevant employee’s home or holiday home, where the victim-survivor was a student of a government school falling within the scope of the Terms of Reference

- private settings (such as a private home or vehicle) after the victim-survivor finished primary school, where the victim-survivor was a former student of a government school falling within the scope of the Terms of Reference.

Community sporting settings

The Board of Inquiry received information about allegations of child sexual abuse in relation to several community sporting organisations in Beaumaris and the surrounding areas. The Board of Inquiry also received information about the connection of relevant employees to local sporting organisations about which the Board of Inquiry has not received any allegations of child sexual abuse.

In addition, the Board of Inquiry received information about allegations of child sexual abuse by relevant employees against children from government schools that were within scope in relation to community sporting organisation activities (for example, training for sporting events).

The Board of Inquiry carefully considered this information, which in each case suggested that it was the relevant employee’s status as a teacher during the relevant period that facilitated them introducing these children to, or otherwise being able to access these children during, such community sporting organisation activities. As set out above, given the Board of Inquiry considered the relationship between the government school and the relevant employee had contributed to the risk of child sexual abuse, this meant allegations of child sexual abuse by relevant employees in relation to community sporting organisation activities came within the scope of the Board of Inquiry’s work.

Importantly, this did not mean that the activities of the relevant community sporting organisation itself were within scope. Instead, the Board of Inquiry’s focus was on the accountability of the Department for the conduct of the relevant employees only, including (for example) any sharing of information or other actions by the Department that reflected its knowledge or management of any risks presented by the relevant employees to government school students in that context.

Other information considered relevant to Departmental accountability

The Board of Inquiry received some information about certain relevant employees that fell outside the Terms of Reference. This included information about these relevant employees’ level of (often unfettered) contact with children that continued beyond the relevant period or in settings that fell out of scope (for example, in circumstances where a teacher went on to teach in an independent school).

While the Board of Inquiry could not inquire into these matters, some of this information has been included in parts of this report. The Board of Inquiry considered such information relevant to highlighting the practical consequences of the Department’s failure to act in response to allegations of historical child sexual abuse within government schools. In practice, while some relevant employees may have left their roles as teachers in government schools, they were nonetheless able to continue to leverage their status as a teacher (or former teacher) into roles and opportunities that placed them in trusted positions with children, such as at sporting clubs. Including this information is an important component of clause 3(c) of the Board of Inquiry’s Terms of Reference, concerning the Department’s response at the time of the historical child sexual abuse.

The case of Eloise Worledge

A number of people raised the disappearance of Eloise Worledge with the Board of Inquiry.16 Eloise was eight years old when she went missing from her family home in Beaumaris in 1976.17 Victoria Police conducted an investigation and considered a range of scenarios as part of this investigation, which included the possibility that one or more sex offenders were involved in her disappearance. In 2003, a coroner found that Eloise’s disappearance ‘remains suspicious’ and presumed her to have died, but could not determine exactly where, when or how she did.18

Some victim-survivors and media outlets urged the Board of Inquiry to consider Eloise’s disappearance because:

- Eloise attended Beaumaris Primary School in the 1970s and was known to many victim-survivors. Her disappearance greatly affected the community, and those who spoke with the Board of Inquiry about Eloise clearly recalled her disappearance and how they felt about it as children.

- Eloise went missing in 1976, while two relevant employees were employed at Beaumaris Primary School.

- Media reports suggest police were not aware at the time that employees at Beaumaris Primary School were allegedly sexually abusing children and question whether this information would have altered the course of the police investigation.19

The Board of Inquiry has closely considered all information it received relating to Eloise, including information received in response to Notices to Produce and through private sessions. The information available to the Board of Inquiry did not reveal any connection between Eloise’s disappearance and the matters within the scope of the Terms of Reference.

As at the date of this report, Eloise’s disappearance remains an open investigation by Victoria Police. The Board of Inquiry encourages anyone with information connected to her disappearance to report this to Victoria Police.

Scope relating to support services

The Terms of Reference were specific in clauses 3(a) and (b) about which experiences of child sexual abuse the Board of Inquiry could inquire into and report on. However, clause 3(e) was more broadly framed. It asked the Board of Inquiry to inquire into, report on and make recommendations in relation to the following:

Having regard to other inquiries and reforms that have taken place since the historical child sexual abuse occurred, whether there are effective support services for victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools.20

Given clause 3(e) was not confined to experiences of historical child sexual abuse described in clauses 3(a) and (b), the Board of Inquiry was able to receive and consider information relevant to the effectiveness of support services for victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools more generally (that is, not limited to those who shared experiences of child sexual abuse by relevant employees). Such information is set out in Part D(opens in a new window) of this report.

Concerns expressed about the Terms of Reference

The Board of Inquiry is aware of concerns raised directly with it, and more broadly in the media, about the limits imposed by the Terms of Reference.21 Such concerns were raised after the announcement of the Board of Inquiry and arose from time to time during the course of the inquiry.

The Board of Inquiry understands that some victim-survivor advocates with experiences of child sexual abuse at Beaumaris Primary School and their supporters had hoped for an inquiry that examined experiences of historical child sexual abuse in all Victorian government schools. They considered that although there had been a number of inquiries relating to institutional child sexual abuse over the past decade, historical child sexual abuse in Victorian government schools remained poorly understood. This was because it was considered that those inquiries often focused on abuses in private or religious schools, or related to more recent child sexual abuse.

Other advocates raised the value of the Board of Inquiry in contributing to healing, and expressed the view that this objective, as stated in clause 2(c) of the Order in Council, should not be limited to only some victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in Victorian government schools. The Board of Inquiry heard from stakeholders that members of the victim-survivor community had experienced distress as a result of the limits on which experiences of historical child sexual abuse could be considered by the Board of Inquiry.

These concerns were expressed in a publicly released statement on 28 November 2023.22 The Chair of the Board of Inquiry wrote to the Premier about them on 30 November 2023.

The Board of Inquiry understands the concerns about its scope. However, while the Terms of Reference are narrow, it is hoped that the work of the Board of Inquiry will nonetheless have broad benefits for victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools. The approach taken by the Board of Inquiry may also prove useful for any other inquiries or processes that may be established in the future in relation to the wider cohort of victim-survivors.

Chapter 3 Endnotes

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 3.

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 3(a)–(f).

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 3.2.

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 3.3 (definition of ‘in a government school’).

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 3.3 (definition of ‘relevant employee’).

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 3.3 (definition of ‘historical child sexual abuse’).

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 3.3 (definition of ‘relevant employee’).

- See Chapter 11, The alleged perpetrators, for further identifying details about these relevant employees.

- The name ‘Wyatt’ is a pseudonym; Order of the Board of Inquiry, Restricted Publication Order, 15 November 2023.

- Notice to Produce served on the Department of Education, 24 October 2023, 4 [6] – 5 [11].

- Document prepared by the Victorian Department of Education in response to a Notice to Produce, ‘Allegations, Complaints, Notifications or Reports in relation to Historical Child Sexual Abuse by Two Relevant Employees’, 31 October 2023, 2 [4]; Document prepared by the Victorian Department of Education in response to a Notice to Produce, ‘Past or Current Criminal or Civil Proceedings in relation to Historical Child Sexual Abuse by Two Relevant Employees’, 31 October 2023, 2 [4].

- Document prepared by the Victorian Department of Education in response to a Notice to Produce, ‘Employment Record’, 31 October 2023, 3 [14]–[15]; Document prepared by the Victorian Department of Education in response to a Notice to Produce, ‘Employment Record’, 31 October 2023, 3 [11]–[12].

- The name ‘Kyle’ is a pseudonym; Order of the Board of Inquiry, Restricted Publication Order, 31 January 2024.

- ‘Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Government Schools Begins Public Hearings’, Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools (Media Release, 18 October 2023) <https://www.beaumarisinquiry.vic.gov.au/inquiry-historical-child-sexual-abuse-government-schools-begins-public-hearings>(opens in a new window).

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 3.3 (definition of ‘in a government school’).

- See e.g.: Private session 1; Private session 3.

- John Silvester, ‘Who Stole Eloise?’, The Age (online, 5 June 2003) <https://www.theage.com.au/national/who-stole-eloise-20030705-gdvzpt.html>(opens in a new window); Francis William Hender, State Coroner Victoria, ‘Record of Investigation into Suspected Death’ (Case No 2159/01, 7 July 2003) 2.

- Francis William Hender, State Coroner Victoria, ‘Record of Investigation into Suspected Death’ (Case No 2159/01, 7 July 2003) 3.

- John Silvester, ‘Could the Beaumaris Inquiry Shed Light on This Famous Abduction?, The Age (online, 27 October 2023) <https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/could-the-beaumaris-inquiry-shed-light-on-this-infamous-child-abduction-20231026-p5ef49.html>(opens in a new window).

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 3(e).

- See e.g.: Russell Jackson, ‘Daniel Andrews Announces Inquiry in Response to “Vile, Evil and Incredibly Damaging Abuse” at Beaumaris Primary School’, ABC News (online, 28 June 2023); Mitch Clarke, ‘Board of Inquiry to Investigate Allegations of Historic Child Abuse at Beaumaris Primary School’, Herald Sun (online, 28 June 2023); Brad Rowswell MP, ‘Statement on Board of Inquiry Investigation into Allegations of Historic Child Sexual Abuse at Beaumaris Primary School’ (Media Release, 28 June 2023) <https://www.bradrowswell.com.au/press-coverage/statement-on-board-of-inquiry-investigation-into-allegations-of-historic-child-abuse-at-beaumaris-primary-school>(opens in a new window); Gerard Henderson, ‘Historic Abuse in Public Schools Ignored Too Long’, The Australian (online, 29 July 2023); Angela Sdrinis Legal, ‘Board of Inquiry Announced into Abuse Scandal at Beaumaris Primary School’ (Web Page, 6 June 2023) <https://www.angelasdrinislegal.com.au/2023.06.29-board-of-inquiry-announced-into-abuse-scandal-at-beaumaris-primary-school.html#:~:text=2023.06.-,28%20Board%20of%20Inquiry%20Announced%20into%20Abuse%20Scandal%20at%20Beaumaris,and%20sexually%20abused%20multiple%20students>(opens in a new window).

- National Advisory Committee, ‘Call for the Victorian Government to Expand the Terms of Reference of the Beaumaris Inquiry’, Star Mail (online, 28 November 2023) <https://ferntreegully.mailcommunity.com.au/opinion/2023-11-28/call-for-the-victorian-government-to-expand-the-terms-of-reference-of-the-beaumaris-inquiry/#:~:text=National%20Survivors’%20Day%20(NSD),of%20Education%20is%20ultimately%20responsible(opens in a new window)>; ‘Survivors Call for Beaumaris Abuse Inquiry to Widen’, The Daily Mail (online, 28 November 2023) <https://www.dailymail.co.uk/wires/aap/article-12797593/Survivors-call-Beaumaris-abuse-inquiry-widen.html>(opens in a new window).

Updated